The California Department of Motor Vehicles indicated this week that an updated set of proposed rules for self-driving cars would only require companies that test self-driving cars to notify local authorities about when the testing would occur, but need not ask for permission. Peter Sweatman, predicted that fully autonomous cars will probably be in use for ride-sharing and parcel delivery within 18 months, and according to the California Department of Motor Vehicles, forty-two companies are already testing 285 autonomous vehicles with backup drivers on California roads. Current California rules require a human driver as backup on public roads; however, the updated set of proposed rules may not include a human driver requirement. This disclosure should concern interested parties from several different viewpoints.

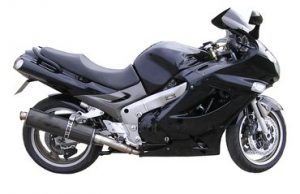

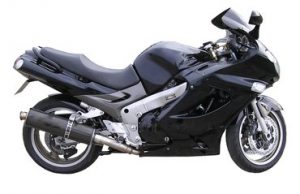

(photo attributed to www.motorauthority.com)

First, safety concerns of pedestrians and other drivers on the road should be the primary focus of inquiry where autonomous vehicles are operated without human oversight. Not only does all technology inevitably malfunction, but the hacking of new technologies has become increasingly prevalent in today’s society. The hacking of consumer data and personal information has been the primary focus recently, but that could change if hackers are given a new target with no human fail-safe in place. For example, the malfunction of a navigation system of an eighteen-wheeler could result in numerous fatalities, particularly in California where the roads are consistently congested. The consequences are largely speculative at this point, but if commercial vehicles full of consumer goods are entirely autonomous, it is plausible to suggest that hackers could enter the vehicles navigation system and alter destinations, or cause the vehicle to crash and destroy the vehicles payload. Such an accident would be widely publicized and would likely have significant impacts on a company’s stock.

Atlanta Personal Injury Lawyer Blog

Atlanta Personal Injury Lawyer Blog